Solids of Revolution Volumes

Lesson Plans > Mathematics > Calculus > Integration > VolumeSlide Show

Lesson Plan/Article

Solids of Revolution Volumes

When calculus students first learn integration, calculating the volumes of solids of revolutions is a great exercise to spend time on, because students can get impressive results readily. One of my favorite activities is to help students derive the formula for the volume of a cone. I sort of steer them toward this result without telling them (at first) where we're going.

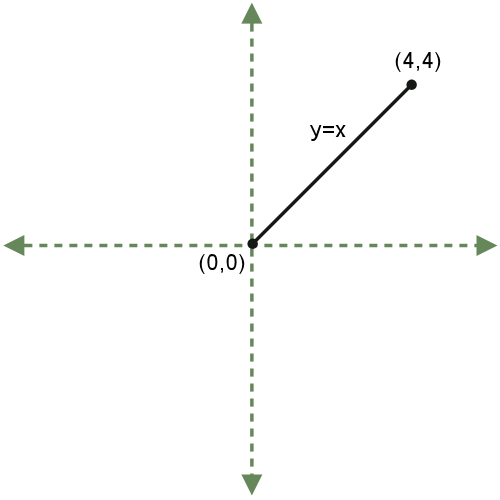

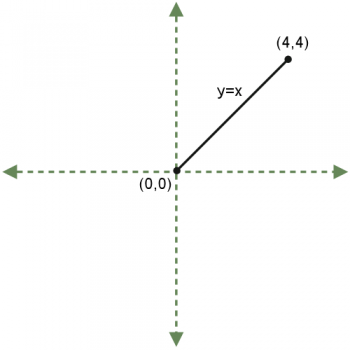

I begin by drawing a cartesian plane, and then graphing y = x on the interval [0,4].

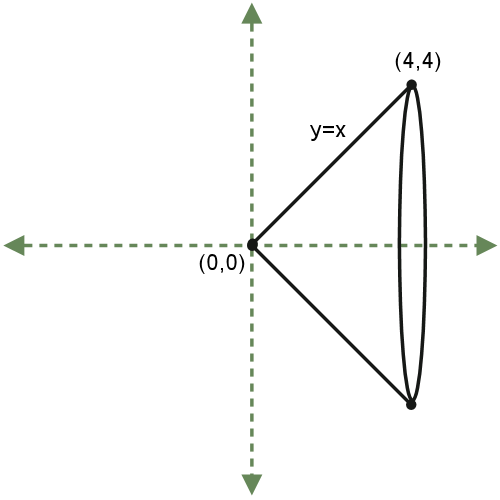

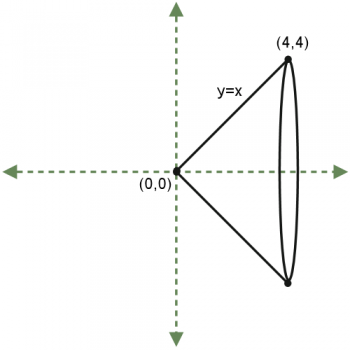

"Suppose I took this line segment and spun it around in a third dimension, around the x-axis. What is the three-dimensional shape I would obtain?"

Usually students figure this out; if they don't I draw in the rotation so they can visualize it better.

"It's a cone."

I tell them that this means a cone is a "solid of revolution," which simply means that we can create it by taking a graph of a function and rotating it around the x-axis. "What is the shape of a cross-section of this cone?" The answer, of course, is "a circle."

Now we review what we know about circles; the area of a circle is given by the function A(r) = pr2.

This is going to be a helpful function, because to find the volume, we just need to integrate the cross-sectional areas along the given interval.

V(x) =

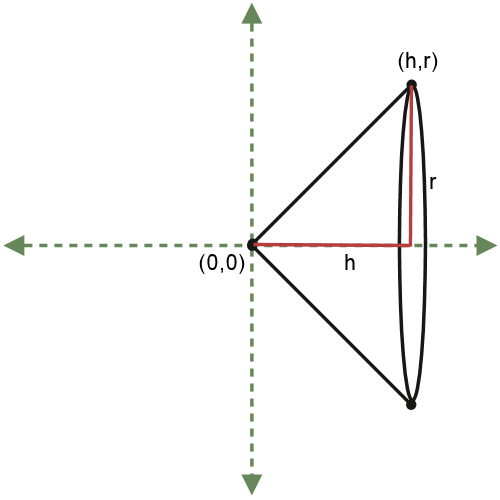

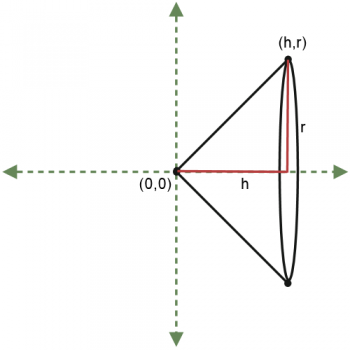

I point out that we found the volume of a specific cone (a cone with base radius = 4 and height = 4). If we want to find a general formula, we just need to start with a "general" cone - one in which we don't assign a specific radius and height. In other words, we just use variables r and h to represent these quantities.

The big issue we have here is that instead of starting with an equation of a line, we've started with two segment lengths. This means we don't know the equation of the line (it's not y = x any more!). Without that equation, we can't find the cross-sectional area, which means we can't integrate. So we need to find the equation of the line connecting (0,0) and (h,r).

This is not difficult; the line passes through the origin, so it has 0 as its y-intercept. Its slope is m =My hope in teaching this lesson is to get students excited to see how some results (like the volume of a cone formula) that they just accepted without questioning in a geometry class, they now have the tools to actually derive for themselves. I tell them that we can use the same techniques to derive formulas for volumes of frustrums and cylinders, which are also solids of revolution.

I spend some time doing additional exercises, like finding the volume when y = x2 is rotated around the x-axis (and also, for good measure, when it is rotated around the y-axis), and then I set them loose on some problems to try on their own.